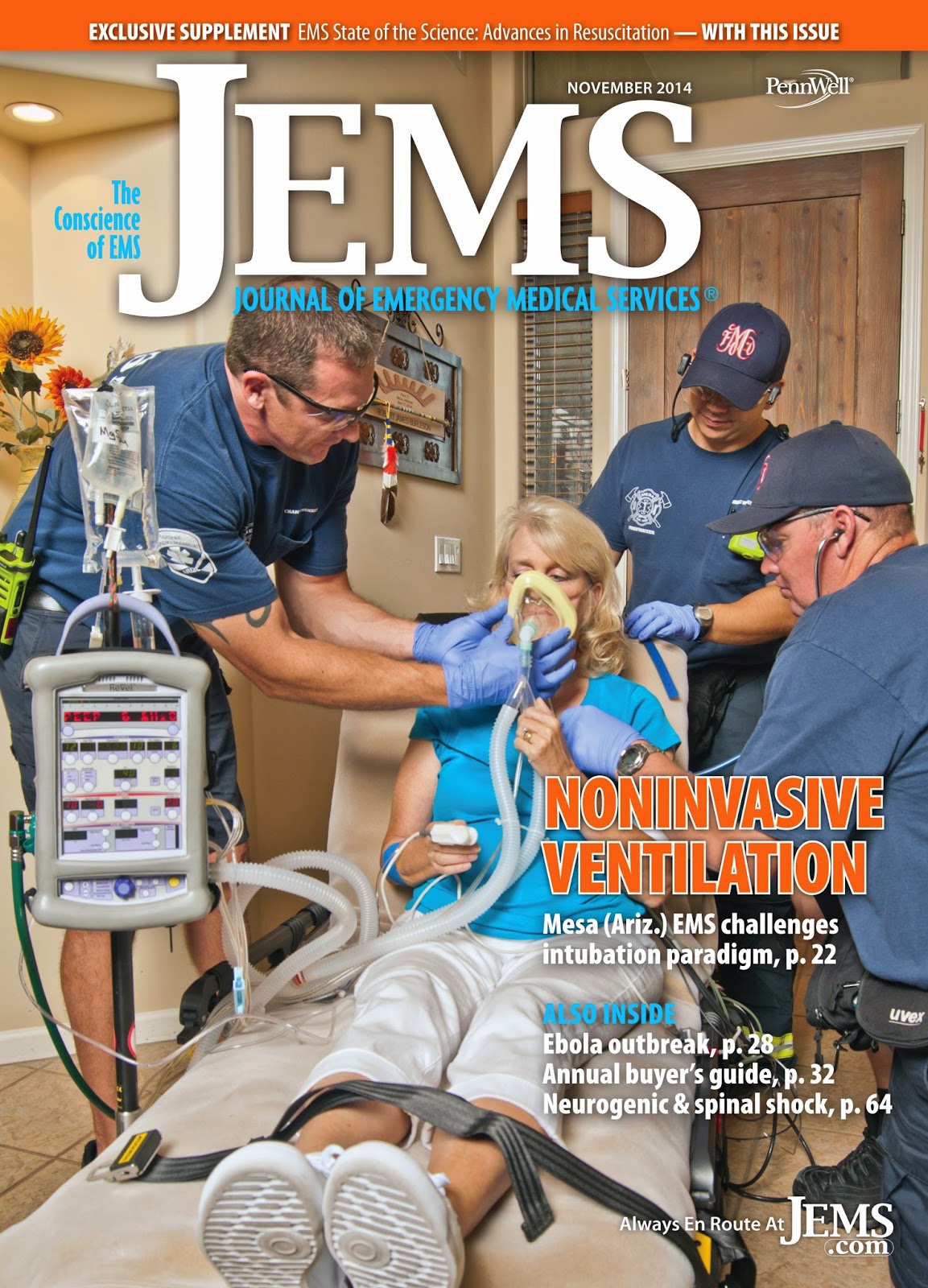

Mesa Fire & Medical Department for JEMS Magazine

|

| JEMS Magazine, November 2014 cover with Mesa Fire & Medical Department. |

Back in September I had the opportunity to work with Mesa Fire and Medical Department on a cover shoot for JEMS magazine. My work takes

me to wherever my assignments or subjects may be, so having the chance to shoot

in my own city was wonderful, plus, being able to represent the ‘home-team’ was

a bonus.

MFMD’s Randy Budd submitted an article to JEMS about the

groundbreaking technology they pioneered in non-invasive positive pressure

ventilation and the editors decided to bump it up to their November cover

story. As is pretty typical in these assignments, I was contacted about the shoot

a week before the deadline, was put in touch with Randy, and pretty much left

on my own to schedule the shoot day and complete the assignment.

With Randy being my point of contact with Mesa Fire and

Medical, I sent an initial email to introduce myself and get a feel for when he

and MFMD may be ready to shoot. Next, I asked JEMS magazine for a copy of the

article as part of my pre-production process to research what I’m going to be

shooting. Even when I know what the subject will be, I will always ask for a

copy of the article, if it’s available, to base my shot list off of because

there are often specific details the author refers to that can be critical to

visually representing the subject. In this case, the article described an

emergency call with a very specific patient description, matching the cover and

a spread image with that description was going to be important. Lastly, while

waiting to get a copy of the article, and while waiting to hear back from

Randy, I began researching non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) to

get an idea of what the scenario may entail and begin my preliminary shot list.

Randy and I began going back and forth about various details

that were important to include from both his perspective and from my

perspective, and after a few email exchanges we were able to set a date and

agree on an appropriate location. I had read the article several times by this

point as well, so I had a shot list forming in my head now that the location

was set. The only detail left to confirm was going to be our patient.

The article referred to a fictitious female patient who was

around 60 years old and suffering from COPD, having an aunt in her mid-50s, I

reached out to see if she’d be willing to play the part.

With an age appropriate model, a date, time, and location

set, and a shot list now fully developed, pre-production was done just a couple

of days before our shoot date.

On the day of the shoot I arrived at the house we’d be

utilizing, owned by a colleague of Randy, and was met by the crew of MFMD’s

LT220 and a TRV (an ambulance looking apparatus used on basic medical calls). I

met with them in the living room and walked them through the timeline of the shoot,

the rooms in the house we’d be using, and how I’d like them to go about their

roles. Whenever I’m shooting an assignment for a trade magazine, whether it’s

about emergency medicine, or electricians, or anything else, this pre-shoot

meeting is crucial. Shooting for trade magazines means that every single person

who views these photos will be able to immediately recognize whether the

subjects of the photos are doing things correctly, and will be experts in the

same field as my subjects. Today, that means everyone who views this magazine

cover and spread will know if my firefighter subjects are dressed

appropriately, handling equipment appropriately, and treating our patient

appropriately. It means they will know if my model is expressing the symptoms of

the emergency call correctly, and it means the details visible match everything

else, such as blood pressures, heart rates, oxygen levels, and the pressure

levels of the star of this shoot, the NPPV machine, which need to be

prominently displayed.  Something I talk about in each of these pre-shoot meeting

with my subjects and models, when trade magazines are involved, is that I need

them to treat this pretend scenario as if it were a real-world emergency, I

need their conversations to stay on-topic because I need their facial

expressions to match the scene, and I need them to prepare for and execute

every detail of this case exactly how they would on an actual call. I work like

this for two reasons, first, on an actual call every firefighter and paramedic

knows what they need to do at any given moment of the call, so I don’t have

images of people looking at the camera waiting for me to tell them how I want

their hands or where they should be looking. Secondly, I do this because if

they walk through the scenario one step at a time I end up with people trying

to ‘freeze’ and their rigid arms and frozen expressions give that away every

time. I need it to be real and I need it to look natural.

Something I talk about in each of these pre-shoot meeting

with my subjects and models, when trade magazines are involved, is that I need

them to treat this pretend scenario as if it were a real-world emergency, I

need their conversations to stay on-topic because I need their facial

expressions to match the scene, and I need them to prepare for and execute

every detail of this case exactly how they would on an actual call. I work like

this for two reasons, first, on an actual call every firefighter and paramedic

knows what they need to do at any given moment of the call, so I don’t have

images of people looking at the camera waiting for me to tell them how I want

their hands or where they should be looking. Secondly, I do this because if

they walk through the scenario one step at a time I end up with people trying

to ‘freeze’ and their rigid arms and frozen expressions give that away every

time. I need it to be real and I need it to look natural. When I was comfortable with moving on from the first scene,

of the MFMD crew assessing and treating the patient in the living room, we move

on to the next shot. We pack up the living room scene and set up for a patient

on the stretcher being moved to the ambulance shot. Once the patient is secured

on the stretcher, the equipment is prepped for the new shot and the crew is in

place to continue treating the patient while moving to the ambulance outside, I

begin shooting again. We’ll go from just inside the front door to just arriving

to the back of the ambulance as many times as necessary to dial in the lighting

and the shooting angles until I feel like I have ‘the shot’ from that specific

set.

When I was comfortable with moving on from the first scene,

of the MFMD crew assessing and treating the patient in the living room, we move

on to the next shot. We pack up the living room scene and set up for a patient

on the stretcher being moved to the ambulance shot. Once the patient is secured

on the stretcher, the equipment is prepped for the new shot and the crew is in

place to continue treating the patient while moving to the ambulance outside, I

begin shooting again. We’ll go from just inside the front door to just arriving

to the back of the ambulance as many times as necessary to dial in the lighting

and the shooting angles until I feel like I have ‘the shot’ from that specific

set.

The last shot was going to be the patient, still on the

stretcher, in the back of the ambulance with the treatment being continuous

each step of the way. This last image set I decided to shoot with just natural

light. It was late morning, and with the back doors of the ambulance open,

there was more than enough light available to not need artificial light added

to the scene. Shooting with natural light gave me the freedom to shoot from any

angle without moving lights around, and to get the shot in just one take.

This entire shoot lasted maybe 90 minutes from beginning to

end and I am extremely happy with the results. The crew from Mesa Fire, my

model playing the patient, and Randy being on set to help with the technical

details of the NPPV technology made everything come together smoothly and without

any real hiccups. I want to thank JEMS for the opportunity, Mesa Fire and

Medical Department for their work in moving EMS forward as well as their

professionalism during our shoot, and of course our patient, my aunt, for

agreeing to play along and get tied down to a stretcher with a mask strapped to

her face on the cover of a national magazine.

If you’re a photographer interested in reading more about

the attention to detail required when working for a trade magazine or

commercial assignment, check back to my blog regularly, I’ll be working on a

post about that soon.

Thanks for visiting.

Comments

Post a Comment